On the footsteps of the Serenissima in the vicentine area

It is a 600-year-long story, which we are going to tell you through 8 clues, 8 stops that can each become a journey to explore a cultural heritage you might not expect.

His name was Nicolò Tron, a patrician, great-grandson of the Doge of the same name, who as a young man was ambassador of the Venetian Republic to the English Court. He settled here after the wool merchants of Schio were allowed to produce, in addition to low cloths, high cloths, which were more valuable and costly.

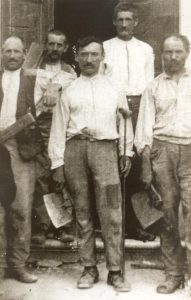

With him we begin the history of the industrialisation of the Vicenza lands, places rich in water and raw materials and inhabited by ingenious people and captains of industry.

The historical centre presents some of the most interesting testimonies of national industrial civilisation that narrate the extraordinary productive and social history of the Rossi family and the historic Lanerossi industry; along the urban route, it is possible to admire various interesting buildings, some of which have been restored, such as the Lanificio Conte, a symbol and seat of work in past centuries.

INFOA city which is better known, is easier to love, that is why we will take you on this pleasant city tour in which your view rises to admire the shapes and façades of interesting palaces and historical buildings, some from the medieval period, others from the Renaissance period of Venetian influence, and some in the neoclassical Palladian style such as Palazzo Fogazzaro through to Art Nouveau. We encounter the beauty of the architects of yesteryear, slowly observing as if it were a visual tasting.

INFOA project assigned to Bonfanti and Zardini, already authors of the Social City, in the 1930s by Gaetano Marzotto, it is incomplete, but it is possible to recognise the monumental entrances, the large stairs, the stone and graniglia balustrades of the terraces, the tree-lined avenue, the greenhouses and the romantic park.

INFOThis footbridge led to the factory and was crossed on foot, as it was the most common way to get to work.

INFOHowever, the lowland forest has long since disappeared and Schio, 'though often called villa [...] is a large land and village', and it cost the people of Schio no small effort to obtain the title of 'land' from Venice in order to distinguish themselves from the other localities, where only agricultural activity was practised.

The church houses an interesting fresco inside with the theme of the forbidden trades on Sunday.

Silver was also the gazeta, worth two money

, and it was the price at which messages with a public function were paid for and distributed. By custom, the bulletins were then called gazettes, the origin of newspaper information.

An easy, two-hour route to places where quartz was mined and through the mineralogical area of contrada Pozzani.

The route offers an extensive visit to what remains of an area heavily exploited for mining, in a naturalistic context of undoubted interest. There is also the possibility of shortening the route. https://www.museialtovicentino.it/pubblicazione/sentiero-geologico-mineralogico/

Designed by Giovanni Maria Baccin in 1791. It was obtained by renovating a building dating back to 1638, and was built exclusively for the production of ceramic mixtures and glazes, i.e. to grind the quartz and calcium carbonate pebbles found in the nearby Brenta riverbed, and to crush and pulverise the frits, glazes and glazes. Upon Baccin's death in 1817, the mill was inherited by the Cecchetto family, remaining in operation until 1960. In 1965 it was purchased by the ceramist Carlo Stringa, who oversaw its restoration and maintenance. The north plant, driven by the large wheel, retains two batteries of steel pestle crushers; the south plant, built almost exclusively of hard wood, carries out the crushing of 'frits' and their subsequent grinding and reduction to fine powder. Today, it is the oldest working example of this type in Europe. It has been under monumental protection by the Ministry of Culture since 1991.

INFOThe Palazzo was erected at the end of the 18th century by the ceramic entrepreneur Giovanni Maria Baccin, who, thanks to a brilliant career within the Antonibon factory, had managed to accumulate considerable capital, so much so that he was able to purchase houses, land, farms, waterworks, a country villa and found his own company for the production of earthenware for English use. What we now call Palazzo Baccin is only a part of the Casa Dominicale inhabited by the family and a priest, 'master here in my house of this school in Le Nove', attended by the ceramists' children to receive an education. The palazzo then, now a Bibliomuseum, housed the first school in Nove between the late 18th and early 19th century, which was started and supported privately. Towards the end of the 19th century, after passing between various heirs, the property began to be divided up and sold off, until the enterprise begun in 1922 by three Novese ceramists: Teodoro Sebellin, Sebastiano Zanolli and Alessandro Zarpellon, who intended to found their own factory and who, attracted by the palazzo and its position, undertook a series of acquisitions that allowed them to reunite almost the entire original building complex. In 1923, the façade was enriched with a grandiose allegorical frieze in painted and glazed earthenware, created by 'Doro' Sebellin, depicting a theory of putti playing with geese and supporting festoons of polychrome flowers and fruit. The work was intended to manifest professionalism capable of offering guarantees of reliability to future clients, like a great business card. Each tile is a different piece from the others, modelled by hand, thanks to a technique learnt while working alongside Prof. Luigi Fabris on the cladding of the façade of the Hotel Hungaria on the Venice Lido. In the second two decades of the 20th century, the factory reached its peak, counting over three thousand models in its catalogue. The 'tosi factory', so called because of the young age of the three entrepreneurs, produced ceramics artistic and modern, ranging from Baroque shapes to Art Nouveau and Art Deco motifs. The production of alpine-inspired figures, figures in typical European costumes, playful compositions with humanised dogs, and female figures inspired by contemporary fashion were all distinctive. In the second half of the 1950s, the manufacture experienced a new lease of life thanks to collaboration with various designers, winning the Palladio Prize in 1962 and in 1973 with Pompeo Pianezzola.

INFOThe union between the "Giuseppe De Fabris" Ceramic Museum and the Nove Art Institute was born in 1875 thanks to the legacy of the sculptor of the same name. Thus began the history of this Museum, unique within a school institution, now the Art Institute, which has one of the richest collections of ceramic works in the area. The pieces - the oldest date back to 1600 - trace the entire history and evolution of ceramics up to the present day. The various directors, who have succeeded one another at the helm of the Institute, and the generous donations of fellow citizens have created a collection that accompanies us from ancient plates and sculptures to works of contemporary art, to which must be added the results of the five international ceramic symposia. Original is Cai Guo-Qiang's collection 'Chinese Terracotta from the 48th Venice Biennale' from 1999. 1875 By the testamentary will of the Novese sculptor Giuseppe de Fabris, the School of Drawing and Plastics Applied to Ceramics was founded in Nove 1890 Becomes the Royal 'G. De Fabris' School of Art 1925 The Museum of Ancient Novese Ceramics is inaugurated on the Institute premises 1954 Becomes 2nd Grade Art School. Upon completion of the three-year course, the Master of Art diploma is obtained 1961 The Art School is transformed into the State Art Institute for Ceramics, with annexed Middle School 1970 The course of studies becomes five-year in duration. On completion of the course, the Applied Art Maturity Diploma is obtained 1979 The section for Architectural and Furniture Designers is activated 1981 The School's current premises are inaugurated, designed by Franco Albini, where the Ceramics Museum also finds new and more suitable accommodation. 1988 The Institute joins the National Plan for Information Technology 1991 With the inauguration of the new wing, the Institute is further enlarged and takes on its current and definitive physiognomy 1995 The experiment led by the Ministry of Education, known as the "Michelangelo Project", begins. The curriculum is modernised and completed with the inclusion of new disciplines 1996 The 'Liceo d'Arte' experimentation begins, involving the unification of Art Institutes and Art Schools. The ISA in Nove is the only school in the province to implement the Artistic Education reform.

INFOIn the eight sections into which the 74 large panels are divided, Alessio Tasca retraces the history of Nove and its ceramics, mixing personal memories with experiences of the past, linked to the months of the year, with a long series of drawn stoneware panels engraved in 1991, commissioned by the municipal administration to decorate the south wall of the Antonibon-Barettoni complex. Before the current wall, there was a pictorial decoration in 1956, executed by the same artist with coloured mortars. Born in Nove in 1929, he graduated from the Art Institute in Venice and followed a master's degree in Florence. In 1948, together with his brothers Marco and Flavio, he founded Tasca Artigiani Ceramisti. In 1961 he opened his own atelier and dedicated himself to the forging of large one-off pieces. Alongside his artistic activity, he taught at the Art Institute of Nove for over twenty years.

INFOIt is the oldest ceramic factory in Italy with uninterrupted activity since 1727. The complex gathers the production departments, the print shop with the original 18th-century specimens, the wood-burning sheds, a large 19th-century circular kiln with four feeding mouths, and the manor house that was already inhabited in the 16th century and is now used as an exhibition hall. In 1732 the Antonibon family obtained from the Senate of the Serenissima special privileges, exemptions from duties and the right to open a shop in Venice, becoming the most important factory in the Venetian Republic not only for the production of majolica, but also porcelain (from 1762) and earthenware for English use (from 1786). In 1907 it was acquired by lawyer Lodovico Barettoni, whose family still owns it today and continues its activity.

INFOThe decorative glazed refractory panel was modelled and decorated by Pompeo Pianezzola in 1952 and placed on the south side of the first branch of the former Banca Popolare di Marostica; it was detached and re-positioned with the same location in the new building in 2000. In the various squares that compose it, one finds references to the semi-industrial manufacture of ceramics next to the agricultural one, the family care next to a representation of fortune with a cornucopia, the potter next to the farm labourer, closed at the bottom by a bee on a honeycomb, the traditional symbol of wealth. Born in Nove in 1925, he began his career as an apprentice at 'Antonibon-Barettoni' and studied at the G. De Fabris Art Institute, where he taught from 1945 to 1977, taking over as director from 1963 to 1968. He graduated in Painting at the Venice Academy. He died in Marostica in 2012.

INFOThe large panel is made of refractory plates and single-fired metal salts, modelled and decorated by Giuseppe Lucietti and placed on the south-east façade of the historic 'Cafè Roma', on the corner of Via Molini and Via Rizzi, in 1992. The decoration recalls and reinterprets the vigorous and intrusive ivy that extended over the building's façade before the restoration. Born in Nove in 1936, he learned the art of ceramics from his family. He studied at the Art Institute in Nove, a pupil of Andrea Parini, and attended the Art Academy in Venice. In the 1950s he stayed in Faenza several times, where he collaborated with Nanni Valentini at Carlo Zauli's workshop. In 1984, he won the Faenza Prize at the 42nd International Competition of Ceramic Art.

INFOThe history of Nove, a town located on the right bank of the Brenta River in the Bassano plain, a few kilometres from Marostica, originates from the river, which here, in the north-eastern part of the province of Vicenza, acquires its greatest breadth. The very lands of the city were wrested from the waters, hence the toponym the 'Terre Nove' (Nine Lands); it was the proximity of 'la Brenta' that determined the economic fortunes of the city and defined its connotations as a 'land of ceramics'. Of the river, deposits of alluvial materials, sand and gravel, quartz and calcium carbonate pebbles, were used for ceramic mixtures. From the river, hydraulic energy was harnessed to drive mills and their complex machinery used for mixing and preparing the soils and paints. Finally, thanks to the Brenta, wood for the kilns and finished products could be transported. A series of artificial canals were built, the oldest of which is the Roggia Isacchina, already mentioned in some documents from the 14th century. In the 17th century, the growing demand and spread of precious Chinese porcelain in Europe induced Dutch ceramists to imitate its workmanship, invading the markets of the Serenissima as well. The Venetian Senate therefore attempted to remedy the situation in 1728 by stimulating domestic production with tax concessions for those who succeeded in producing porcelain and improving the Majolica. The Antonibon factory was the fifth in Italy to produce porcelain. The 'Didactic Parapet' consists of a series of 11+1 panels of various sizes created by Giulio and Flavio Polloniato, with texts by Nadir Stringa, in 1997 on glazed and decorated tiles placed on the east side of Piazza De Fabris. They illustrate the history of Nove and its ceramics from the 18th to the early 20th century with references to the Art Institute and its most illustrious directors. Plates and other tableware are inserted on the panels, exemplifying the most common decorations in the various eras. The series closes with a map of the town showing the main historical buildings and a list of ceramic companies in the area.

INFO

In the square of Valstagna there is a winged lion displayed right on the clock tower.

INFOThe Calà del Sacco is an ancient route, also used for timber transport, that connects the locality of Sasso, in the Altopiano dei Sette Comuni, with Valstagna, where the logs continued their flow on the Brenta.

Project curated by Ivana De Toni, coordinator of Musei Altovicentino, with the collaboration of Elena Agosti; concept by Alessandra Stella

Texts and research by: Elena Agosti; Alessandro Bertoncello; Angelo Chemin; Luigi Chiminello; Gabriele Dal Zotto; Ivana De Toni; Luciano De Zen; Liana Ferretti; Stefano Lazzarotto; Laura Lunardon; Bernardetta Pallozzi; Alice Pizzato; Ivan Pontarollo; Ketti Pozzan; Luigi Scorzon; Paolo Snichelotto; Alessandra Stella; Loretta Stevan.

Translations by: Aurora Faggionato

Images: Altovicentino Collections/Museums

Graphics: Studio 375 of Thiene(VI)

Video: Walter Ronzani of Schio (VI)

It is a 600-year-long story, which we are going to tell you through 8 clues, 8 stops that can each become a journey to explore a cultural heritage you might not expect.

Nicolò Tron, a Venetian patrician in Schio

MarcoCrosara, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

MarcoCrosara, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsIn the 18th century, a Venetian entrepreneur wanted to set up his factory in Schio.

His name was Nicolò Tron, a patrician, great-grandson of the Doge of the same name, who as a young man was ambassador of the Venetian Republic to the English Court. He settled here after the wool merchants of Schio were allowed to produce, in addition to low cloths, high cloths, which were more valuable and costly.

With him we begin the history of the industrialisation of the Vicenza lands, places rich in water and raw materials and inhabited by ingenious people and captains of industry.

Terrae Scledi, land of handicraft workshops

The name 'Schio' seems to have originated from scledum, 'ischi', which is a vulgar term for an oak tree or a place planted with oaks. Other places derive their names from plants: according to historian Giovanni Mantese, Valdagno derives from the Latin Vallis Alnei, or 'alder valley', while Malo may derive from the Latin malum, or apple tree.

However, the lowland forest has long since disappeared and Schio, 'though often called villa [...] is a large land and village', and it cost the people of Schio no small effort to obtain the title of 'land' from Venice in order to distinguish themselves from the other localities, where only agricultural activity was practised.

Carnival and Venetian masks

As in any truly hospitable place, there can be no shortage of festivities. And the ancient tradition of Carnival finds a very special form in Malo, as community archivist Giacomo Pozzuolo writes: "another carnival is held here, which is not used in other places, and it is at the time when silk is being worked, with beautiful masks, which are taken to the cookers, holding their reels for a while, until they have seen the mistresses and workers; gifts of flowers also follow; there are also masks that go to the troops, with sounds, and once they have reached the cookers they invite the young workers to dance and then, having given them flowers, they go to other places".

For a silver ducat

Trade required a currency and Venice produced coins that were worth all over Europe and even Asia. They were gold and silver, with the effigies of the Doges, of different thicknesses and weights and therefore with different values. But what we want you to know is that for a certain period, silver was mined in the mines of the Tretto hills.

Silver was also the gazeta, worth two money

, and it was the price at which messages with a public function were paid for and distributed. By custom, the bulletins were then called gazettes, the origin of newspaper information.

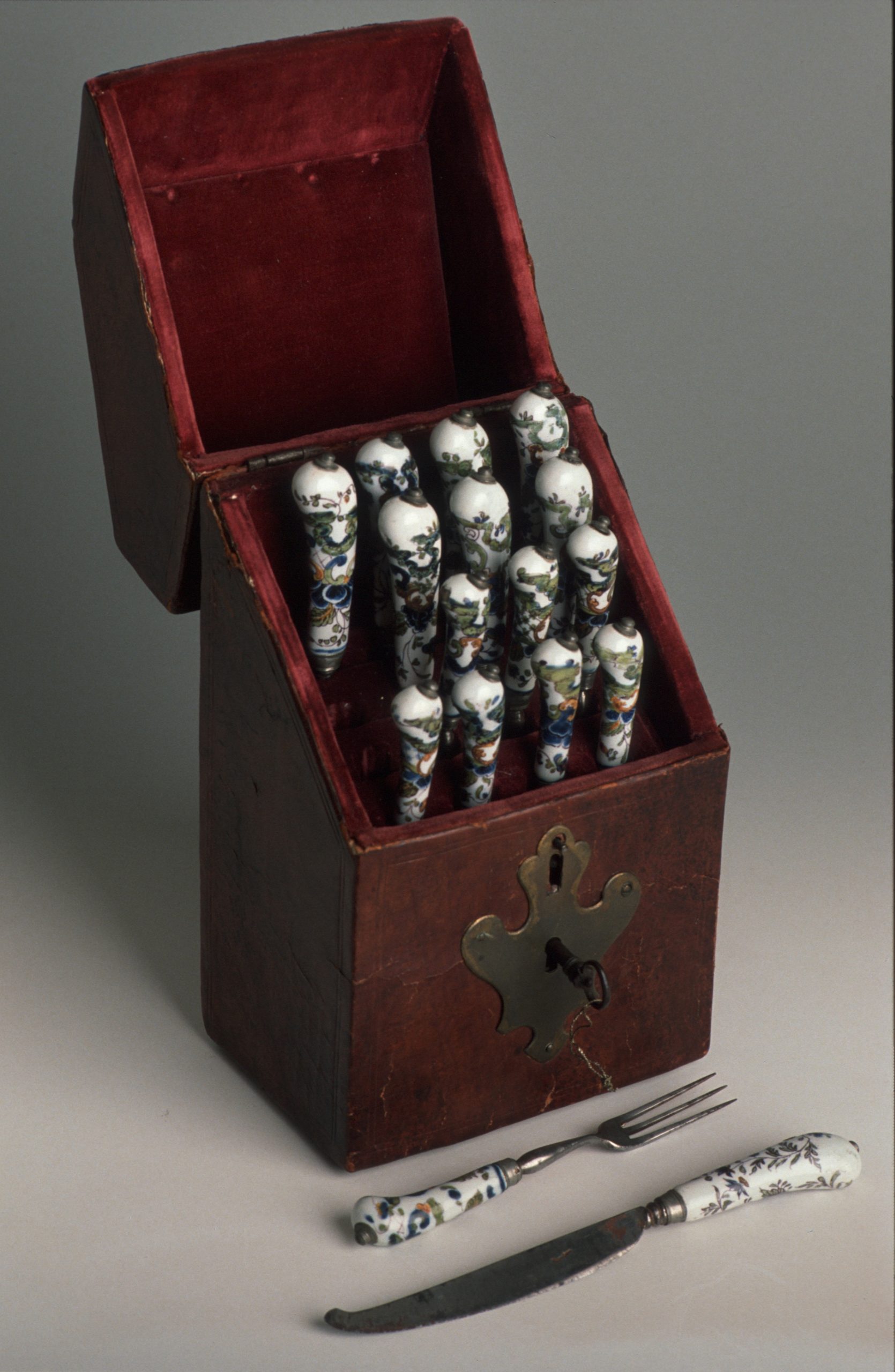

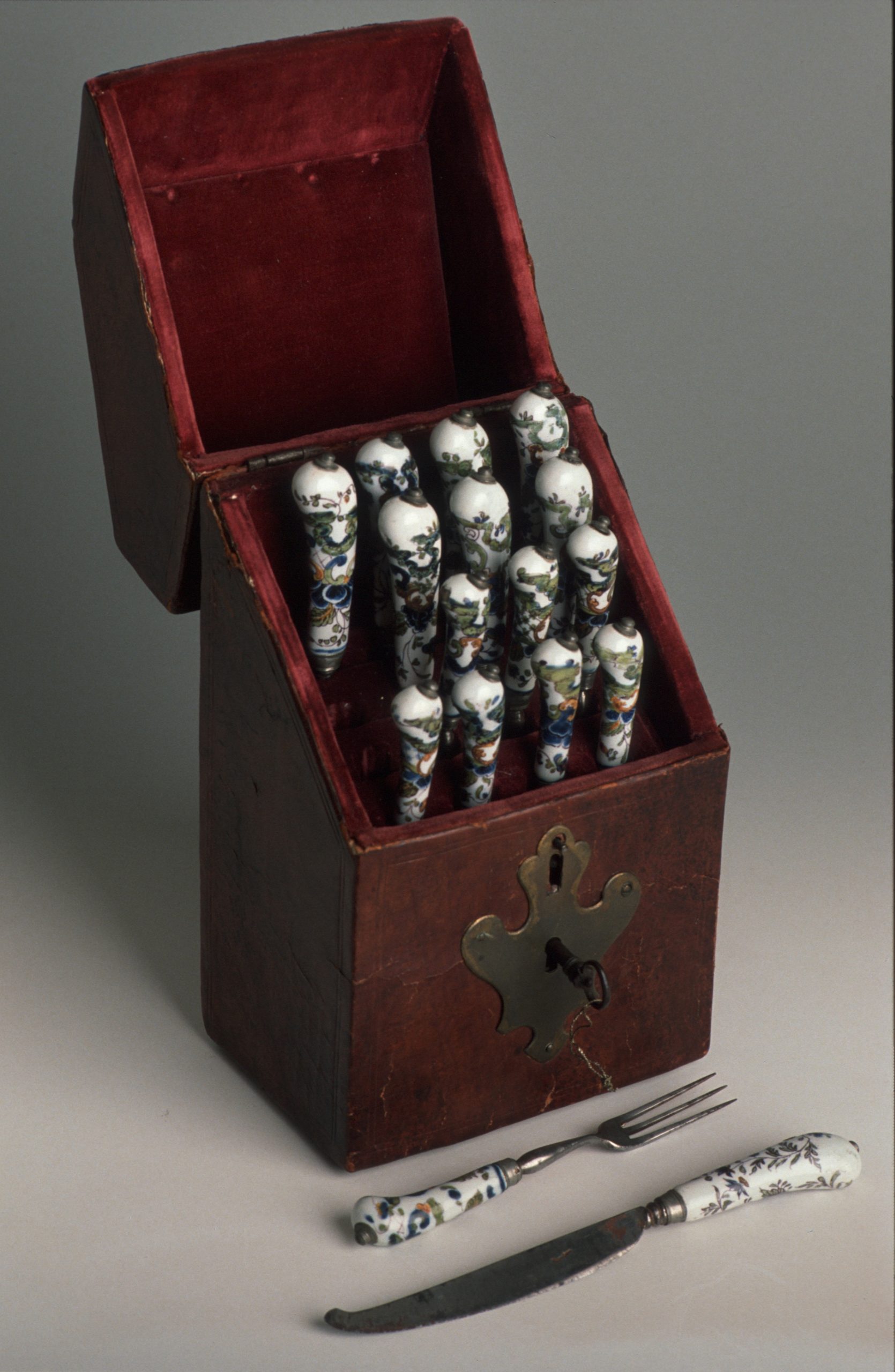

The great table service of the 18th century

The fork, as we use it today, was only introduced into table setting in the 18th century; previously, food was brought to the mouth with the fingers and the two-pronged fork was used, but only in the kitchen. It seems that the Venetians again played some role in the spread of this object, following marriages to oriental women where the fork was widespread, and it was thus reintroduced in Europe. But in the 18th century, the art of setting the table spread to such an extent that more refined tableware production was required, which found its way to Nove.

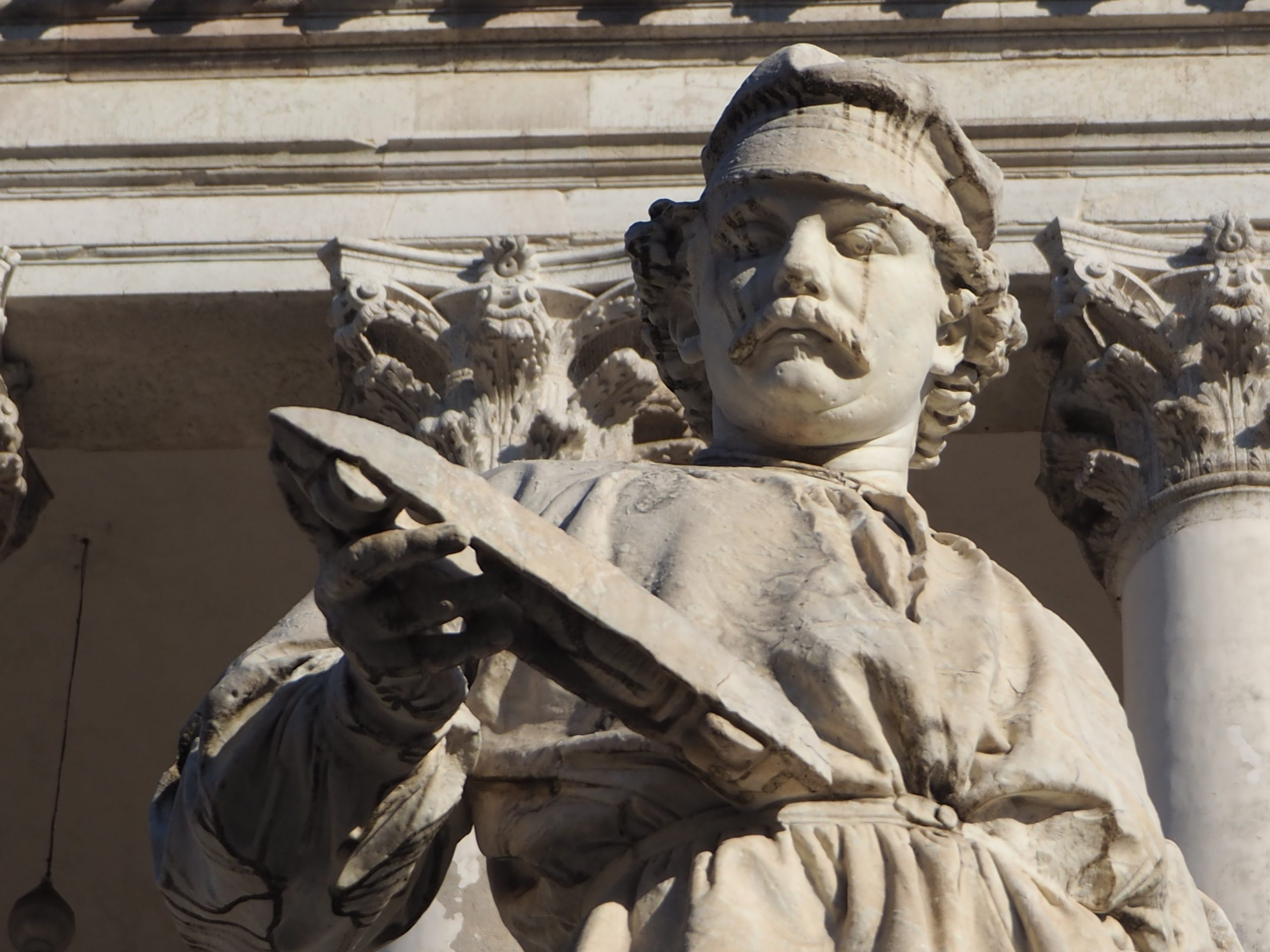

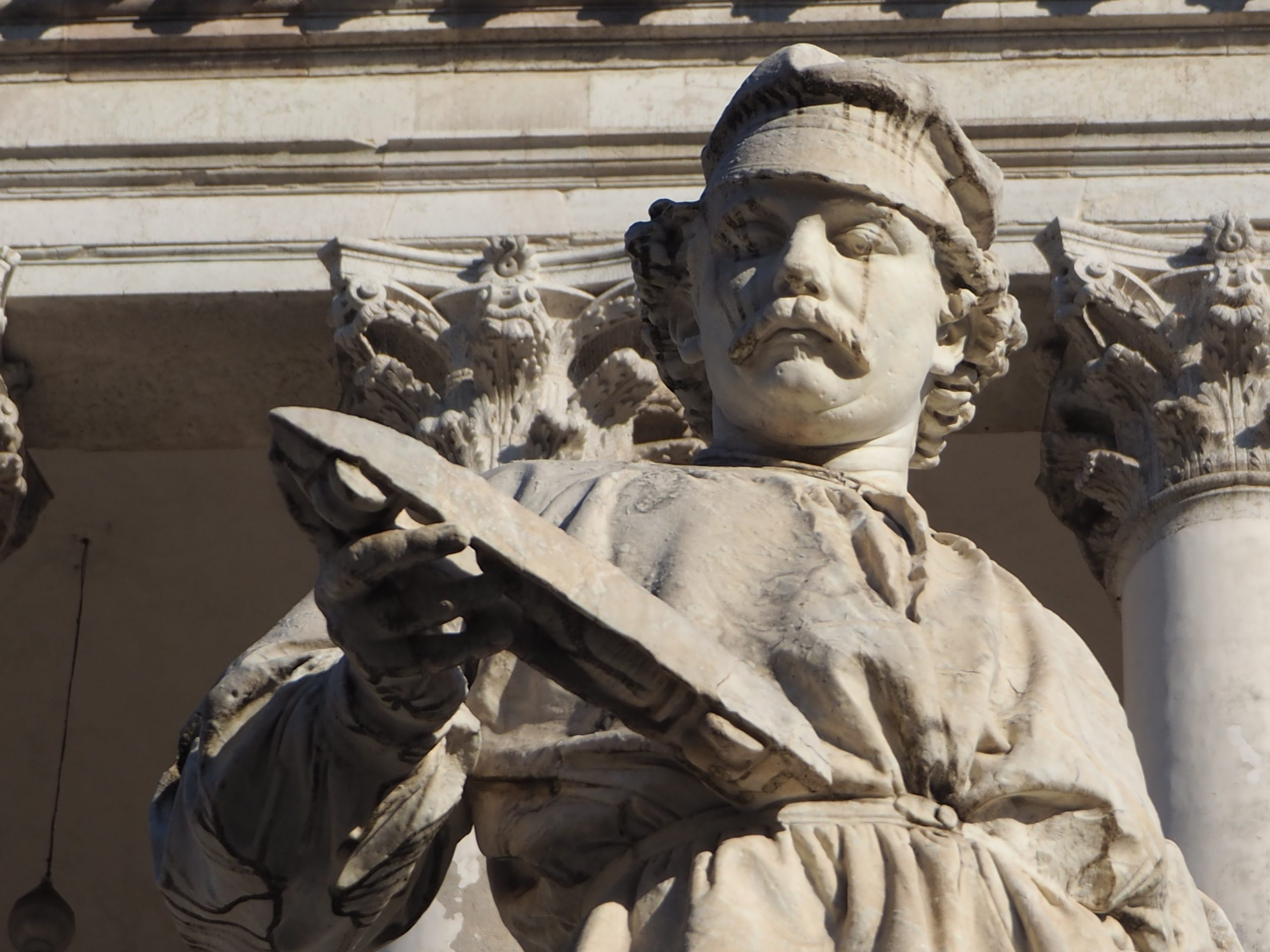

A Venetian Podestà in Marostica

Many towns and villages have had a castle, but only in Marostica is the ancient charm revived. Here, Venice established a Podestà, while in the other villages it installed a Vicario, favouring the prosperity of this place. But we would like to make a stop in the famous Piazza degli Scacchi in honour of Prospero Alpini, who was born in Marostica and then went to Padua to study medicine. It was in this way that he happened to become the personal physician to the ambassador of the Serenissima in Cairo, where he studied medicinal plants, including coffee…

The Remondini library in Venice

In the early 16th century, more than half of all books published in the Italian peninsula were printed in Venice. The art of printing with movable type invented by Gutemberg in the mid-15th century in Germany was immediately imported to the lagune city, where the customs tax on the import of books had already been abolished in 1443, effectively favouring trade. Now, thanks to movable type, books could be produced in a greater number of copies than manuscripts and sold at prices affordable to most. The development of this flourishing industry also required the supply of raw material, namely paper. But it is easy to say paper if one does not know the variety of types and formats available, which were produced along the River Oileros.

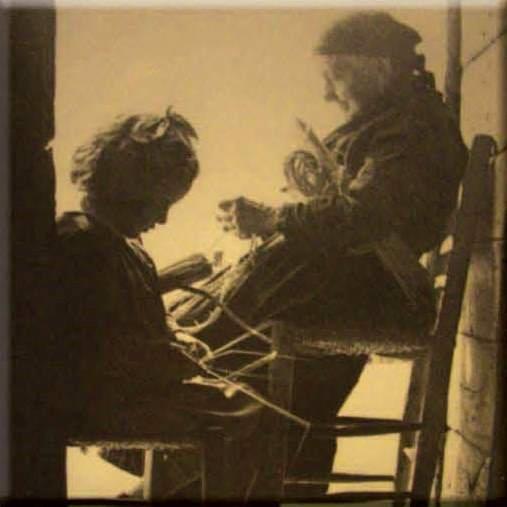

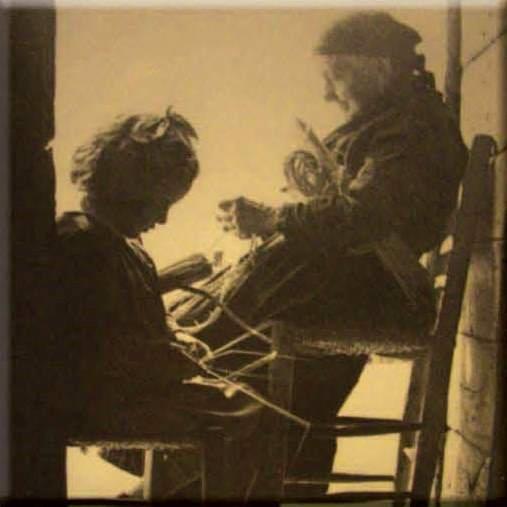

Straw, an art from the far Orient?

There are many love stories, which have a tormented beginning and pass through tumultuous events before the happy ending. The story of Nicoletto Dal Sasso and his love for the beautiful Bettina is just of this kind and has as its happy ending not only the crowning of the dream of love, but also the learning of a refined and precious art, such as that of making straw hats, learnt during a forced stay in the eastern dominions of the Serenissima.